Read Chapters 1 & 2 of the textbook and read the paper regarding the Trial of T. Hall. From the paper, begin your reading on page 14 with the first full paragraph and end the reading after the completion of the first paragraph on page 17. Once all reading is complete, respond to the following items:

- Why was T. Hall singled out for scrutiny?

- How did T. Hall’s neighbors respond to the gossip that this person’s sex was unclear?

- What authority did women claim in assessing the situation?

- What authority did men claim?

- What does the struggle to T. Hall’s gender identity suggest about the structure of community life and the roles of men and women in colonial America?

You are required to submit an initial posting (200 words minimum) that addresses the items above. You are also expected to respond to the posting of at least one other student (100 words minimum). Your response should address why you agree/disagree with their posting, support it with new evidence to bring a new perspective to the topic. Do NOT submit anything as an attachment since some people cannot open certain formats.

***CTC BLACKBOARD: UN:c1849946 PW:Jamayap2021

I. Introduction

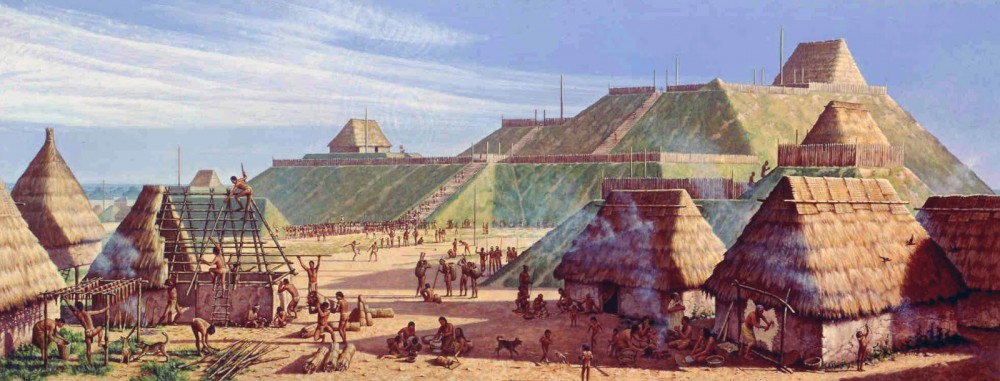

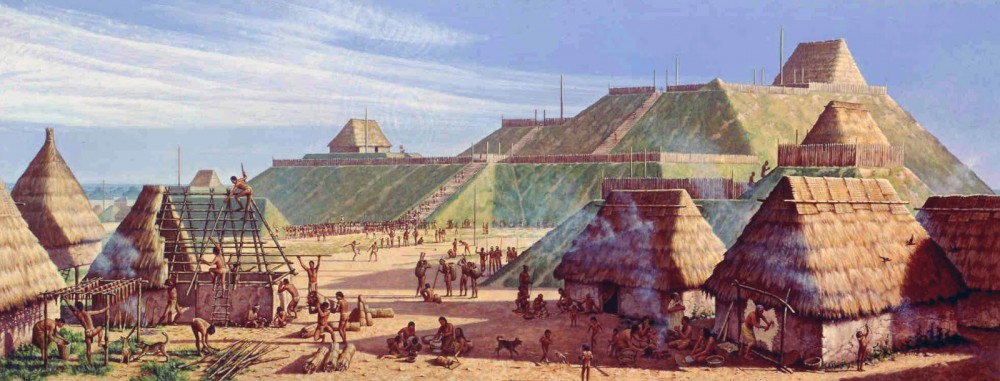

Europeans called the Americas “the New World.” But for the millions of Native Americans they encountered, it was anything but. Humans have lived in the Americas for over ten thousand years. Dynamic and diverse, they spoke hundreds of languages and created thousands of distinct cultures. Native Americans built settled communities and followed seasonal migration patterns, maintained peace through alliances and warred with their neighbors, and developed self-sufficient economies and maintained vast trade networks. They cultivated distinct art forms and spiritual values. Kinship ties knit their communities together. But the arrival of Europeans and the resulting global exchange of people, animals, plants, and microbes—what scholars benignly call the Columbian Exchange—bridged more than ten thousand years of geographic separation, inaugurated centuries of violence, unleashed the greatest biological terror the world had ever seen, and revolutionized the history of the world. It began one of the most consequential developments in all of human history and the first chapter in the long American yawp.

II. The First Americans

American history begins with the first Americans. But where do their stories start? Native Americans passed stories down through the millennia that tell of their creation and reveal the contours of Indigenous belief. The Salinan people of present-day California, for example, tell of a bald eagle that formed the first man out of clay and the first woman out of a feather. According to a Lenape tradition, the earth was made when Sky Woman fell into a watery world and, with the help of muskrat and beaver, landed safely on a turtle’s back, thus creating Turtle Island, or North America. A Choctaw tradition locates southeastern peoples’ beginnings inside the great Mother Mound earthwork, Nunih Waya, in the lower Mississippi Valley. Nahua people trace their beginnings to the place of the Seven Caves, from which their ancestors emerged before they migrated to what is now central Mexico. America’s Indigenous peoples have passed down many accounts of their origins, written and oral, which share creation and migration histories.

Archaeologists and anthropologists, meanwhile, focus on migration histories. Studying artifacts, bones, and genetic signatures, these scholars have pieced together a narrative that claims that the Americas were once a “new world” for Native Americans as well.

The last global ice age trapped much of the world’s water in enormous continental glaciers. Twenty thousand years ago, ice sheets, some a mile thick, extended across North America as far south as modern-day Illinois. With so much of the world’s water captured in these massive ice sheets, global sea levels were much lower, and a land bridge connected Asia and North America across the Bering Strait. Between twelve and twenty thousand years ago, Native ancestors crossed the ice, waters, and exposed lands between the continents of Asia and America. These mobile hunter-gatherers traveled in small bands, exploiting vegetable, animal, and marine resources into the Beringian tundra at the northwestern edge of North America. DNA evidence suggests that these ancestors paused—for perhaps fifteen thousand years—in the expansive region between Asia and America. Other ancestors crossed the seas and voyaged along the Pacific coast, traveling along riverways and settling where local ecosystems permitted. Glacial sheets receded around fourteen thousand years ago, opening a corridor to warmer climates and new resources. Some ancestral communities migrated southward and eastward. Evidence found at Monte Verde, a site in modern-day Chile, suggests that human activity began there at least 14,500 years ago. Similar evidence hints at human settlement in the Florida panhandle and in Central Texas at the same time. On many points, archaeological and traditional knowledge sources converge: the dental, archaeological, linguistic, oral, ecological, and genetic evidence illustrates a great deal of diversity, with numerous groups settling and migrating over thousands of years, potentially from many different points of origin. Whether emerging from the earth, water, or sky; being made by a creator; or migrating to their homelands, modern Native American communities recount histories in America that date long before human memory.

In the Northwest, Native groups exploited the great salmon-filled rivers. On the plains and prairie lands, hunting communities followed bison herds and moved according to seasonal patterns. In mountains, prairies, deserts, and forests, the cultures and ways of life of paleo-era ancestors were as varied as the geography. These groups spoke hundreds of languages and adopted distinct cultural practices. Rich and diverse diets fueled massive population growth across the continent.

Agriculture arose sometime between nine thousand and five thousand years ago, almost simultaneously in the Eastern and Western Hemispheres. Mesoamericans in modern-day Mexico and Central America relied on domesticated maize (corn) to develop the hemisphere’s first settled population around 1200 BCE. Corn was high in caloric content, easily dried and stored, and, in Mesoamerica’s warm and fertile Gulf Coast, could sometimes be harvested twice in a year. Corn—as well as other Mesoamerican crops—spread across North America and continues to hold an important spiritual and cultural place in many Native communities.

Gender roles in Colonial America Hartman 14

simply a sinful and illegal act if not a marker of modern sexual orientation. A sexual

revolution produced a third gender- the new sodomites. Prior to 1700, there had been two

genders of male and female. After 1700, there were now three genders; man, woman and

sodomite.50 Even if a person was considered a sodomite, he still had equal rights

applicable to a male. The Puritans wanted more males in their society- so they allowed

Sodomy to pass without punishment as long as it did not happen to be brought out in

public, disrupting the ‘natural’ course of events in a village. If a man was “ousted” it

made the other men seem weak, and brought a smear to the overall masculinity and

virility of the male gender in the village. So naturally, Puritan men took it seriously when

it came to proving their masculinity. A man would concern himself primarily with the

judgments of other men.51

Mary Beth Norton brings up the role gender plays in seventeenth-century

America in Searchers Again Assembled, concerning the interesting case of T. Hall, a

hermaphrodite (or intersexed) individual. Christened and raised as a girl, Thomasine had

a clear identity as a female and adopted that gender role in society during childhood.

Upon reaching adulthood, Thomasine shed the gender role of a woman and adopted the

gender role of Thomas in 1625, taking the place of a brother after his death in the army.

Upon returning to Plymouth in 1627 after his service in France, Hall resumed his identity

as Thomasine, supporting herself by using her needlework skills. Upon learning of a ship

traveling to Virginia, Hall decided to become Thomas again for the journey to the

Virginia colony as an indentured servant. A man named John Tyos took on the role of

Thomas’s master by December 1627/8, showing that Hall chose to continue his role as

Thomas in Virginia. Although, court records show that Thomas chose to dress as a

woman at some point in time during his stay in Virginia. The court records are not clear

on the issue of whether or not Hall continued as a female after January 1628. John Tyos

sold Hall, legally considered a maidservant named Thomasine to John Atkins around

January 1628. The court records of T’s trial do not answer the question of what happened

to raise questions about T’s sexual identity.52 Court records show T’s answer to the

question about why T would wear women’s clothing when he was a male to be: “I goe in

50 Harvey, Karen.

51 Norton, Mary Beth. Gender & Defamation in Maryland, pg. 37

52 Norton, pg 70

Gender roles in Colonial America Hartman 15

weoman’s apparel to get a bitt for my Catt.”53 In the seventeenth century, it was

possible to interpret the remark made by T in crude sexual terms; T was dressing as a

woman to get sex from men. It was not clear in the trial transcripts whether or not that the

court chose to apply the sexualized meaning, or the literal meaning, to T’s trial.

Regardless of the context of T’s “Catt”, his behavior was considered disruptive to the

community, so T had to be brought before court to explain himself.

Due to confusions about T. Hall’s sexuality, he was brought to court in order to

determine what role his gender played in society. His sexuality had no revelation to the

court unless it threatened the ideals of gender the colonists held. The colonists wanted a

clear definition of T’s gender so T could be placed in the ‘proper’ category and become

liable for his behaviors under whichever laws applied to his to be determined gender. T’s

situation brings to light that for the colonists, gender had two possible determinants;

physical and cultural. Physical was determined by nature of one’s genitalia, and cultural

was the character of one’s knowledge and one’s manner of behaving. Gender was one of

the two most basic determinants of role in the early modern world.54 Men and Women

each had their own role, complete with rules and expectations for their gender. A crucial

identifier of a person’s role in the society of seventeenth-century America would be their

clothing. If one wore skirts and dresses, the person was clearly identified and put into the

role of a woman. T. Hall makes liberal use of either role by his cross-dressing, thus

bringing confusion to the community T was part of. The case record raises issues of

sexuality rather than of biological sex or of gendered behavior.55 T was stripped of any

rights as a human being through the process. T could not ‘belong’ to either gendered

group.

Gender was clearly physically and aesthetically defined in the seventeenth

century. T. Hall acted like a woman and physically resembled a man; violating every

possible concept concerning masculinity and feminity in the Puritan community.

Confusion rose among the community as to what gender he was, and what role he played

out in society based on the clash of the two ideals concerning gender. After several

examinations of which probably violated T’s privacy both physically and mentally, the

53 Norton, pg. 71

54 Norton, p. 73

55 Norton, p. 75

Gender roles in Colonial America Hartman 16

court still couldn’t come to amends regarding T’s physical gender. To men, Thomasine

was not a male due to the fact that her male organs didn’t have the ability to function

properly. Thomasine was sterile, unable to produce children, or get a woman pregnant.

To the males of the town, T was in essence, a female, and considered to fit that role.

Women were viewed as inferior to of men, and their sexual organs were regarded as

internal versions of male genitalia. The women who examined T and were part of the trial

concluded that Thomas was male based on the presence of male genitalia. For the

women, the anatomy of T. Hall was more important than the feminine qualities presented.

It is clear that different concepts concerning the biological aspect of gender drove a rift

between the sexes during the trial.56

Throughout the trial of T Hall, many of the key questions about Hall were

couched in terms of what clothing T should wear, men’s or women’s. The judges did not

declare a clear identity of gender, only directed Hall on what apparel they expected T to

wear. In a fundamental sense, seventeenth-century people’s identity was expressed in

their apparel. Virginia, where the trial was taking place, never went so far as

Massachusetts, which passed laws regulating clothing. In an act for Regulating and

Orderly Celebrating of Marriages written in 1640, with revisions made in 1672 and 1702,

there is a passage depicting:.. that if any man shall wear women’s apparel, or if any

woman shall wear men’s apparel, and be thereof duly convicted; such offenders shall be

corporally punished or fined at the discretion of the county court, not exceeding

seventeen dollars.57 In light of this context, it is not much of a surprise that decisions

about the sexual identity of T. Hall were stated in terms of clothing. Clothing was a sharp

distinction of the gender of its wearer, and gender was one of the two mast basic

determinants of role in the early modern world. People who wore skirts nurtured children;

people who wore pants did not.

In the conclusion of the trial before the General Court of the colony of Virginia on

April 8, 1629, it was surprising that the General Court accepted Hall’s self-definition as

both man and woman. The male judges demonstrated their ability to transcend the

categories that determined the thinking of ordinary colonists. Due to their adamant need

56 Karlsen, pg 73.

57 The law of domestic relations: marriage, divorce, dower pg 56

Gender roles in Colonial America Hartman 17

to categorize T, they put him in his own category based on their own perceptions of both

biological and behavioral characteristics of gender. T was finally stripped of his rights as

either gender, and forced to wear both trousers and an apron, signifying the fact that he

held elements of both the male and female.58 The focus on clothing indicates that the

colonists needed a visual symbol of what gender group this individual belonged to. In a

belief system that hypothesized that women were inferior men, any inferior man; one

who could not function in sexual terms, was a woman. Identity of individuals relied

heavily on gender roles, and the judges couldn’t find a better answer to the question

concerning Hall’s gender. The only reason Hall was brought to court was to determine

Hall’s gender and his rights as a member of the male or female gender. The court case

shows the powerful role that gender and the colonial community could play in

individuals’ lives.59

The lives of individuals were thrown into a sense of uncertainty with the

introduction of witchcraft into the court, which had a powerful role within the

community. Clive Holmes shows how women who became involved in the legal process

often held on to un-reported grievances and suspicions.60 In some cases, the additional

testimony offered by women deals with incidents so remote as to rouse the court’s

suspicions concerning the witness’s motives in coming forward.61 Such suspicious

motives can be applied to the accusations concerning Rebecca Nurse. Rebecca was, in the

eyes of those who knew her, the very essence of what a Puritan mother should be; deeply

pious and a devoted mother.62 Rebecca had a hearing loss, which frustrated her in

interactions with her neighbors. A recent event bringing her under scrutiny happened

when Rebecca had lost her temper over a misunderstanding with a neighbor, and the

neighbor died soon after. The wife of the un-named neighbor couldn’t stop talking about

the argument as if there was a cause and effect involved in the death. The conflict

prompted an interest in Rebecca, and it was not long until the Proctors brought her the

news she had been accused as a witch by Ann Putnam the younger. The Proctors were deeply moved by the reaction of Rebecca.

Talk to us support@bestqualitywriters.com

Talk to us support@bestqualitywriters.com